“I’ve been patient for seven years now . . . can you check when I got locked up?” “That was a long time ago . . . I was little then.”

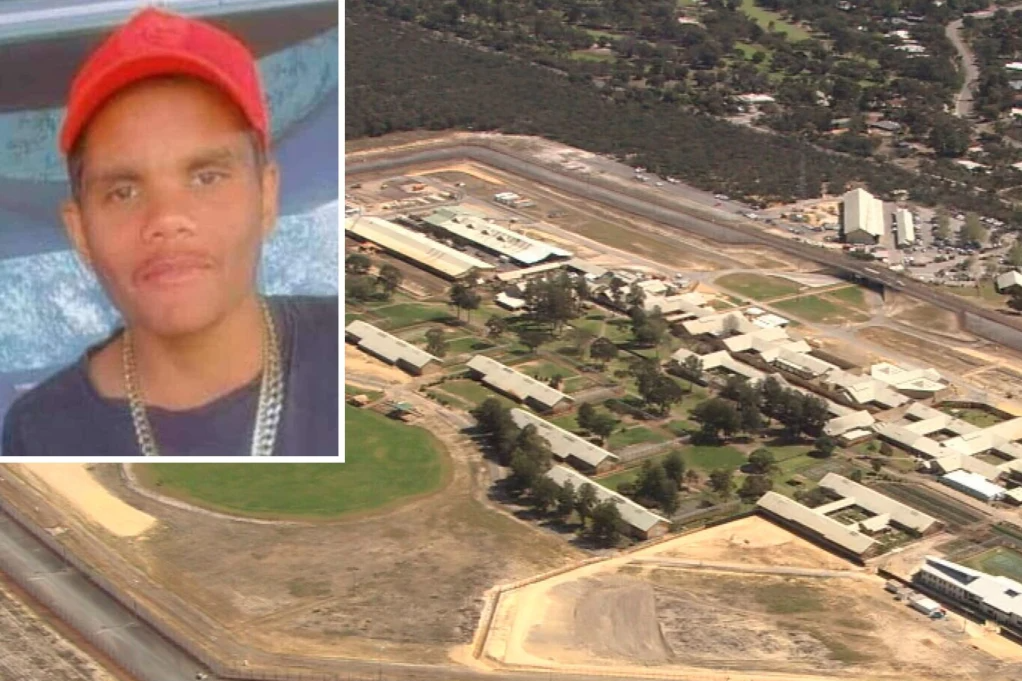

Those were confronting words spoken by Meekatharra teenager Cleveland Dodd to a youth custodial officer on the October 2023 night he fatally self-harmed in his cell at the makeshift youth wing at Casuarina Prison known as Unit 18. He died days later in hospital.

As the first juvenile in WA to die in custody, Cleveland’s death in October is now subject to a fast-tracked coronial inquest, which started earlier this month.

Evidence has been heard from the first tranche of witnesses, many of them the YCOs dealing with Cleveland on that fateful night, including the officer who found him in his cell.

The inquest began on Wednesday, April 3 and was adjourned on Friday, April 12.

SLOW TO RESPOND

The 16-year-old high-risk detainee threatened to harm himself eight times on his final night in Unit 18, his inquest was told on the first day. He had been let outside his cell twice that day — October 11 — and felt his pleas to speak to a psychologist or mentors were being ignored.

Cleveland also made multiple calls on his intercom asking for water as his cell had no taps because they had been removed after being damaged.

“Everyone gives their animals water,” Cleveland’s grandmother Glenda Mippy said outside court.

“Why did they put my grandson in a cell that had no tap?”

While he was not the only detainee to self-harm or threaten to do so that day, the inquest was told Cleveland’s final warning was just two words: “I’m through.”

However, detainees made such remarks so frequently, it was suspected custodial officers were desensitised.

Video footage shows an officer walking at a leisurely pace after Cleveland was found hanging.

Other revelations to shock Cleveland’s family include one officer putting on his boots and buttoning up his uniform before responding; guards not carrying radios; the CCTV camera in Cleveland’s cell being left covered with wet toilet paper for all but 23 seconds of 11 hours that day; and it taking nine minutes for paramedics to see Cleveland after arriving at the facility.

‘I THOUGHT HE WAS PLAYING SOME SORT OF TRICK’

The YCO who found Cleveland in his cell, Daniel Torrijos, was the first witness called and claimed he did not run to alert authorities because he had arthritic knees, and he did not call out for help because he was in shock and focused on that one task.

Mr Torrijos said he had been talking with a different detainee — who had also tried to take his own life — earlier that day, and tried to extricate himself from that conversation to peer into Cleveland’s cell.

He said at first, he thought “I was seeing things”.

“I thought he was playing some sort of trick. I looked at his face and it was still,” Mr Torrijos said.

“I couldn’t really believe what I was seeing. He was definitely gone.”

Mr Torrijos said he walked “as quick as I could go” to alert his senior officer, Kyle Mead-Hunter.

First he had to turn the light on in the office of Mr Mead-Hunter, who appeared to be emerging “from a reclined position”, counsel assisting the Coroner Anthony Crocker said in his opening address.

Mr Mead-Hunter, who has been suspended from duty, had been in a darkened room and appeared to be putting on his boots and buttoning up his shirt when the alarm was raised about Cleveland

“I was just in shock. I don’t know,” Mr Torrijos replied when asked why he didn’t again ask for help on his return to Cleveland’s cell. “I was just focused on getting (access to the cell). I just wanted to get him down.”

Mr Torrijos, like other officers on shift that night, was not wearing a radio — a breach of Department of Justice policy.

If they had been carrying their radios, he could have called in a code red medical emergency, Coroner Phil Urquhart pointed out.

Mr Torrijos said Unit 18 was perceived by his colleagues as “set up to fail”.

The unit was created within the maximum-security adult male Casuarina Prison in July 2022 after a massive riot at Banksia Hill.

The cells in Unit 18 were so damaged they were “unliveable”, Mr Torrijos told the inquest. Despite complaints from staff, “no one listened to us”, he said.

“We were travelling blind a lot of the time at Unit 18,” he said.

“It was an accident waiting to happen.

“We just tried to function as best as we could.”

Mr Torrijos and Mr Mead-Hunter had both previously faced disciplinary action for breaching professional standards, the inquest was told.

Mr Torrijos was fined in 2021 after CCTV footage of him performing a night shift at Banksia Hill revealed he had not performed seven cell checks, despite “tick and flick” reports indicating he had.

Cell check records for that shift were ticked from 7.15pm until 6am despite Cleveland being taken to hospital about 2.30am.

Mr Torrijos told the inquest threats from juvenile detainees were “constant”, the vast majority were “not serious” and, while checked not all were recorded because “you’d be writing things down all night long”.

Mr Mead-Hunter was disciplined a month before Cleveland’s death, but details of his indiscretion have not yet been revealed. He is due to give evidence during the inquest’s second sitting.

After his grilling, Mr Torrijos said: “It’s a tragedy . . . obviously could have been avoided. It’s a build-up of things over the years.”

SOCIAL MEDIA & MOVIES

During the evidence of another YCO, Nina Hayden, it emerged Mr Mead-Hunter was found to have breached department policy by using YouTube, Instagram and a chat forum for “over four hours straight” while on duty in January last year.

He was also found to have contravened the code of conduct by going into an office, closing the door, and turning a light off, emerging more than an hour later.

Ms Hayden was also questioned about three calls Cleveland made to her on his in-cell intercom on the night of the tragedy, saying he had a headache and wanted to see nurse Fiona Bain.

Cleveland was told by Ms Hayden during the final call — a little over an hour before he was found having self-harmed — that she had asked the nurse to “come up” and to “be patient”.

“I just can’t recall when,” Ms Hayden said.

Asked if she referred to Cleveland when she spoke to Ms Bain, Ms Hayden said: “I just remember speaking to her.”

After being told to be patient, the 16-year-old said to Ms Hayden: “I’ve been patient for seven years now . . . can you check when I got locked up?” When the answer came, he said: “That was a long time ago . . . I was little then.”

At that point, Cleveland’s heartbroken mother Nadene Dodd left the courtroom in tears.

When asked if his reflective words gave her any extra cause for concern, Ms Hayden said: “We had conversations about different things. He didn’t just talk to us to complain.”

Ms Hayden told the inquest she was “nervous” about acting as a senior officer despite still being on probation, and admitted she was not aware of various Unit 18 policies. She said she had been given no training and about two hours notice before being thrust into an acting senior role.

Ms Hayden also admitted YCOs were not told about a detainee’s status on a system that rated their risk of self-harm — known as the At-Risk Management System — and had to look the information up for themselves.

UNIT 18 ‘INHUMANE’

Ms Bain, the nurse on duty that night, told the inquest she was so affected by what she had seen at Unit 18 that she kept a diary for her “own mental health”, testifying the facility was “inhumane”.

The diary contained descriptions of the high-security unit “like being in a war zone”, with “huge” staff turnover and fewer experienced staff leading to “incidents”.

“I’m literally here to pick up the pieces,” she wrote.

Ms Bain, who Cleveland asked to see that fateful night, agreed the diary helped her process what she had seen at work.

She described the cells as “disgusting” and said some of the boys having no running water in their quarters where they ate and used the toilet was “an appalling state of affairs”.

Coroner Phil Urquhart pressed further, asking if she would go so far as to label Unit 18 “inhumane”, and she concurred.

Because no code red was called, Ms Bain did not bring medical equipment the first time she went to Cleveland’s cell.

Ms Bain wept in court and stood as she apologised to Cleveland’s family at the conclusion of her testimony.

In her statement, Ms Bain described Unit 18 as a “leaky boat” destined to sink “no matter how much you patch it up”.

“That’s an overwhelming understatement,” the coroner remarked.

Ms Bain said she did not recall a lot about that night, but said the entire Unit 18 population would be on suicide watch if policies for ARMS were followed to the letter.

Ms Bain said threats by detainees were frequent — “there could be 50 of them a day” — but some were clearly not serious.

“We’ve had weekends where we’ve had to deal with a detainee continually self-harming for hours and hours on end and having no access to mental health,” she said.

Outside court, asked if she had anything to say to the family, Ms Bain said: “That I’m sorry.”

Day shift unit manager Christina Mitchell said providing the level of supervision a child on ARMS required was “very difficult”, with detainees covering up their in-cell CCTV cameras and door hatches.

“It was quite impossible, really,” Ms Mitchell said.

“I felt helpless that I couldn’t control what was going on.”

Ms Mitchell said rolling lockdowns meant detainees often only had an hour a day out of their cells, pacing the halls of their wing because they couldn’t go outside.

“I couldn’t stay in one of those cells for 23 hours a day,” she said.

PRELIMINARY FINDING

Mr Urquhart said he was satisfied with the way guards and Ms Bain tried to save Cleveland.

He told the court he was “putting aside other matters” that went on in the notorious unit within Casuarina Prison on the night Cleveland took steps to end his own life in his cell.

These included the 16-year-old threatening to self-harm eight times before being discovered, and repeatedly asking to see nurse Fiona Bain, to no avail.

‘EVERY CELL A SUICIDE RISK’

The inquest was told every cell in Unit 18 had damage that detainees could have used to inflict injuries on themselves.

A damaged air vent in the ceiling has been linked to Cleveland’s fatal injury.

The unit’s management team was aware of the damage and it was scheduled for repair on October 11, but that did not happen.

“At that moment in time there were obstructions around why we couldn’t move certain people,” Ms Mitchell said.

Mr Urquhart said he inspected Unit 18 after the teen died, and found damage to the air vents in seven of the 16 cells he examined.

A SHATTERED FAMILY

Cleveland’s family and supporters have been at the inquest, listening to their evidence and at times watching harrowing CCTV footage, hopeful this painful process will lead to meaningful change in the juvenile justice system.

Mr Urquhart granted a request by Cleveland’s mother to view, in private, body-worn camera footage of him being resuscitated and transported to hospital.

The teen’s father, Wayne Gentle, has been watching the inquest via video link from Greenough Regional Prison after a bid for early parole was denied.

It emerged during the inquest that a letter Cleveland had written to his father in August last year had failed to be sent to him. Mr Urquhart told the inquest Mr Gentle would receive a letter of apology and he would be wanting answers as to why he had never received that letter.

Outside court, Cleveland’s aunt Bonnie Gentle said the family had seen the teen’s cell and it “wasn’t fit for any kid”.

“While Cleveland lay in that cell gasping for breath to save himself, they strolled down the hallway,” Ms Mippy said. “They just took their time. No one was running around, no one was panicking. Nothing.”

The inquest has been told Cleveland’s childhood was marred by exposure to domestic violence, drugs and antisocial crowds, and he had been diagnosed with major depressive disorder. He was detained for the first time at the age of 12.

The inquest will resume on July 22.

Lifeline: 13 11 14

13YARN (13 92 76)