Transfer of Banksia Hill detainees to Casuarina Prison a sign of a ‘broken’ system, retired judge says

Originally published on abc.net.au written by Rhiannon Shine

The longest-serving president of Western Australia’s children’s court has slammed the state’s youth justice system as “broken” and “a basket case”.

Warning: This story contains distressing content

Mr Reynolds, who served as president of the Children’s Court of Western Australia for 14 years, was also one of the longest-serving judicial officers in the nation.

“Sad to say I think the system’s broken,” he told 7.30.

“And I would say it compromises the work of the Children’s Court.

“As a sitting judge and magistrate, if you have to decide on whether or not a child is sentenced to a period of detention, and that person’s going to go to a facility where he or she is going to be treated harshly, inhumanely and possibly unlawfully, it weighs heavily on your mind.”

Mr Reynolds said the situation at Banksia Hill Detention Centre — WA’s sole youth detention facility — had deteriorated over the last decade.

“The court doesn’t have, and I ceased to have, confidence in the department in delivering proper rehabilitation programs to the children,” he said.

“And you may not, at the end of the day, impose the sentence of detention, when otherwise you may have.

“That’s serious because then when the child goes back into the community, they haven’t received the rehabilitation supports, [and] they go back into the community more disconnected, more rejected, angrier, and more aggressive, and more likely to commit an offence.”

‘When you want to make a monster, this is how you do it’

Mr Reynolds’ comments echoed the sentiment of current Children’s Court president Hylton Quail, who earlier this year warned “when you treat a damaged child like an animal, they will behave like an animal”.

“When you want to make a monster, this is how you do it,” Judge Quail said when sentencing a 15-year-old who had assaulted youth custodial officers.

On July 21 this year, Judge Quail described the experience of a 13-year-old child at Banksia Hill over the preceding month as “harsh, punitive and of no rehabilitative effect”.

“Of greater concern, that is the second time this week that I have come to that conclusion in sentencing a young Aboriginal child at Banksia Hill,” Judge Quail said.

The boy was being sentenced for burglaries he committed when he was 11, 12, and 13 years old.

His father was in prison and his mother died when he was six years old.

According to the boy’s detention management report read out in court, he was “very keen to learn” and had undertaken extra work in his cell while in Banksia Hill.

His teachers reported that the boy had been enthused about learning, was focused, and consistently demonstrated good behaviour.

But rolling lockdowns due to staff shortages in June and July this year meant the boy’s access to education and counselling had to be wound back and his behaviour deteriorated, so he wound up in the Intensive Supervision Unit (ISU) after acting out and threatening self-harm.

In June he had around 12 hours of education, and in July he had just five hours.

This was compared with an expectation of four and a half hours of schooling each day for a child in detention – which would equate to 135 hours for the month.

“The conditions of [the boy’s] detention have not met the minimum standards the community and court expects and the law requires,” Judge Quail said.

“I’m satisfied that [his] deteriorating behaviour in detention is directly linked to the conditions of his detention, the lengthy lockdowns he has been subject to, the failure to provide him with psychological care, education programs, stimulation, and consistent support.”

‘Kids leave worse than when they went in’

In April, WA’s prisons watchdog outlined “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” of youth detainees in the detention centre’s ISU, which is where detainees behaving badly or at risk of self-harm are placed.

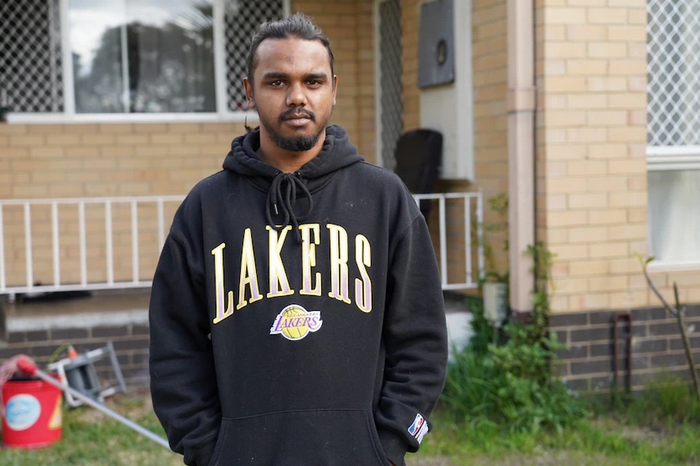

Former Banksia Hill detainee Nikkea Graham spent time in the ISU, which detainees referred to as “down back”, when he was a teenager.

Both of his parents died when he was a child, and he became homeless and started stealing.

Mr Graham said he spent two weeks in the ISU, where he was permitted limited time out of his cell to walk around a small exercise area which he referred to as a “birdcage”.

“When you put a dog in a cage and grow it up like that, you let it out one day [and] that thing is vicious,” he said.

“Same with a person. You leave them in the cell locked up for a certain amount of time, it’s going to click.

“Especially when you’re young because you’re not even fully developed yet.”

Restorative justice advocate Gerry Georgatos helped Mr Graham find his feet after he got out of Banksia.

“Nikkea’s circumstance was that he was homeless, he was an orphan, and so were some of his siblings,” Mr Georgatos said.

“They had no-one to turn to. Where were the services there for them?

“We gave him the nurture that he wasn’t getting and that is why he is in a better place today.”

Mr Graham is among around 500 current and former youth detainees in Western Australia who have given statements as part of a class-action lawsuit alleging mistreatment at the centre.

Lawyer Dana Levitt said the key allegation made in the class action, which was yet to be filed in the Federal Court, was that Banksia Hill was not fit for purpose and therefore had a detrimental impact on every child who entered it.

“Rather than youth justice being rehabilitative or restorative, kids leave worse than they went in,” Ms Levitt said.

Ms Levitt said allegations included children being placed in long periods of solitary confinement and being denied access to psychosocial supports such as counselling.

“Which when you consider that nine out of 10 children in Banksia Hill suffers from a disability is even worse,” she said.

“There is an absolute abject lack of youth-centric and culturally-appropriate care inside Banksia Hill.”

A 14-year-old boy who was among those recently moved to the juvenile unit at Casuarina Prison was also a complainant of the class action.

His mother told 7.30 before he was moved, the boy had been in the ISU since May and had been self-harming.

“I am scared that he might keep self-harming,” she said.

“And then I get that phone call – every mother’s worst nightmare.

“I’ve only got one son.”

Kurin Minang Noongar woman Hannah McGlade, who is an expert member of the UN Permanent Forum for Indigenous Issues, said the UN Convention prohibited the placement of children into adult prisons unless it was in the best interests of the child.

“Incarceration is highly damaging and is even leading to deaths in custody, as we saw on the weekend with the death of [an Aboriginal man at Casuarina Prison] who had been incarcerated since childhood at Banksia,” she said.

Former judge recommends regionalised system

Mr Reynolds described the decision to send juveniles to the adult prison, albeit in a secure separate unit, as “appalling” and “the result of long-term ongoing incompetence”.

“The children, and the community as a whole, need and deserve an urgent change to a proper support and rehabilitative model based on mountains of reliable research and internationally recognised human rights,” he said.

The Director General of the Justice Department, Adam Tomison, said the decision to move the children to Casuarina was not one he took lightly.

“In the last four weeks we finally got to a point where these young people were getting out of cells and assaulting staff,” he said.

“Now, at that point, I’ve got no choice but to make some decisions around how I will keep that facility safe.

“For the young people involved, who were doing things like exposing electrical wires and throwing bricks and things at staff, for the staff themselves, but also for the 80-odd young people who aren’t doing anything wrong who are just trying to have a positive experience whilst they are at Banksia Hill.”

Mr Tomison said the detention of juveniles at Casuarina Prison was temporary while a $25 million upgrade of Banksia Hill was being developed.

In 2019-20, Aboriginal children and young people in WA were 36 times more likely than non-Aboriginal children and young people to be held in youth detention.

More than two-thirds of children and young people in detention on an average day are Aboriginal.

In his time as the president of the Children’s Court of Western Australia, Mr Reynolds dealt with thousands of cases and read numerous psychological and psychiatric reports.

He said the idea that a state the size of WA had just one youth detention centre was flawed.

“My view is that what we should have is a regionalised system where we have children and particularly Aboriginal children on country, close to family, close to community,” he said.

“Get them to know themselves, get a sense of their own identity, get a knowledge of their own culture, and then have a good sense of self-worth, and in turn, be good members of the community and render the community safer.”

In May, the WA government announced it would build a dedicated residential facility to house at-risk youth on country.