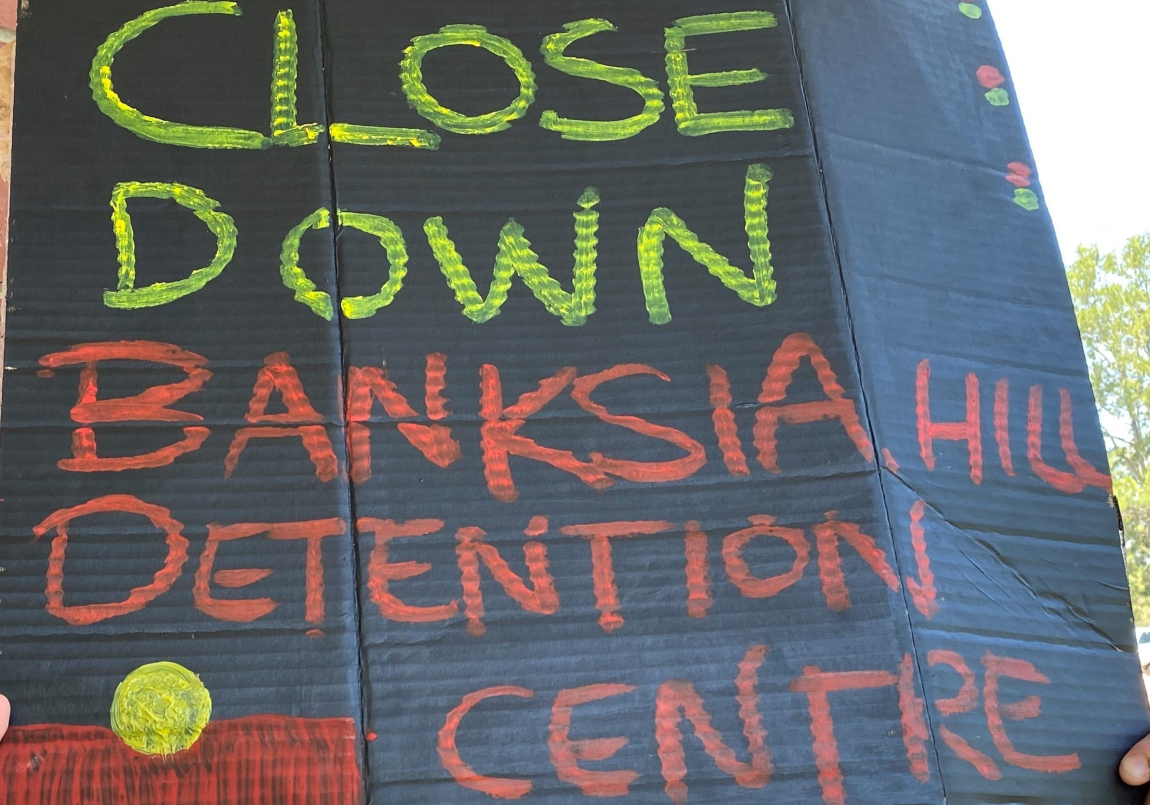

Western Australia’s only youth detention facility is in an “emergency” in which “every element” is failing, the state’s Inspector of Custodial Services says in a report made public Thursday.

Aboriginal youth are radically over-represented in the facility – Banksia Hill.

The Office of Inspector Eamon Ryan noted that the Inspector of Custodial Services Act requires his reports be laid before both Houses of Parliament for at least 30 days before they can be tabled and publicly released.

“This timeframe is substantial. Much can occur in 30 days, particularly when it relates to youth custody in Western Australia which is currently experiencing acute crisis. The report tabled today was laid before both Houses on 8 May 2023, one day prior to the most recent riot at Banksia Hill Detention Centre (9–10 May 2023),” the Office of the Inspector said in a statement.

The report outlines the “three levels of crisis” observed by Mr Ryan when he and his team inspected Banksia Hill and Unit 18 in early February 2023. It was the first full inspection of Banksia Hill since Mr Ryan’s impromptu inspection of the Intensive Support Unit in late 2021.

It was also the first inspection since the Department of Justice gazetted Unit 18 at Casuarina Prison to accommodate some of the young people held in detention.

Mr Ryan said the inspection team included specialist advisers covering education, young people, health and mental health, and cultural safety.

“And we intended to use our experts’ knowledge and advice to examine whether the care being provided to the young people was trauma informed and contemporary. But what we found was an emergency. Every element of Banksia Hill was failing, often through no fault of its own or the efforts of staff. Ultimately, we saw young people, staff and a physical environment in acute crisis,” he said.

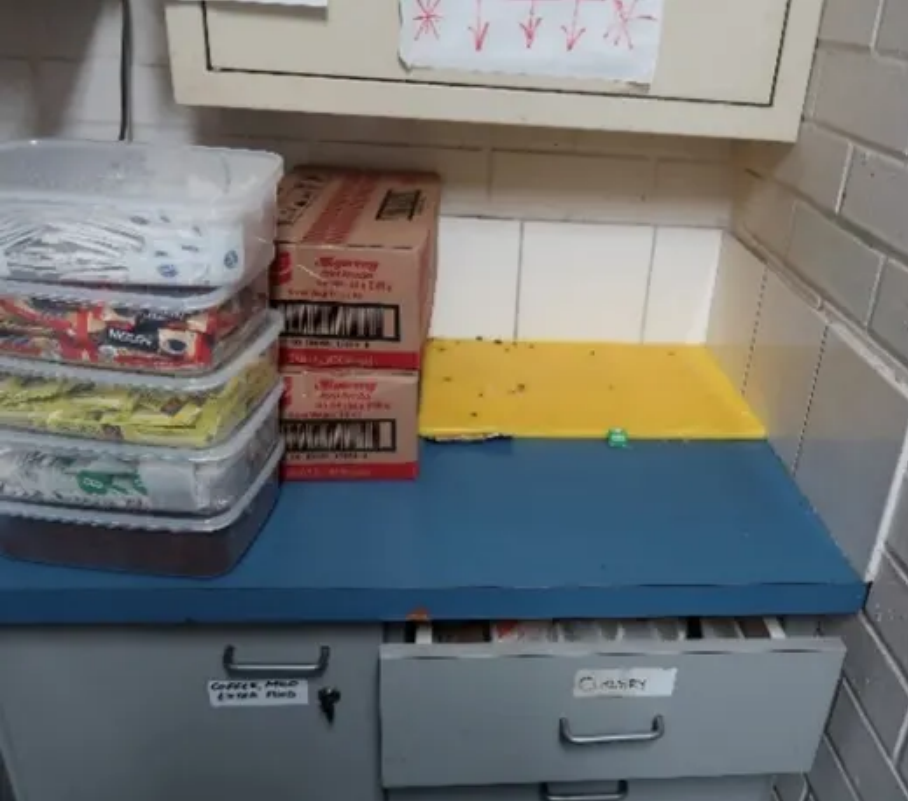

“Site-wide confinement orders were in place at Banksia Hill every day of the 10-day inspection. This meant the young people were locked in cell for excessive lengths of time in order to maintain the good government, good order and security of the centre due to the absence of sufficient staffing.”

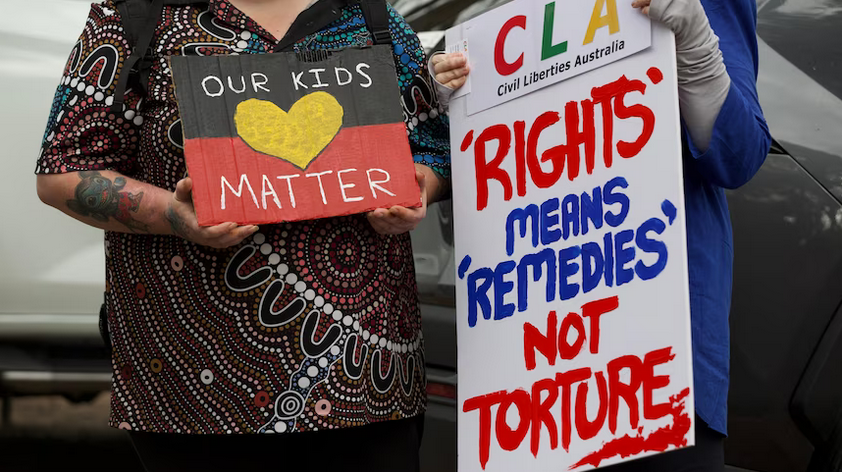

The Aboriginal Legal Service of WA is currently fighting in court to end the excessive use of lockdowns in youth detention, which was deemed unlawful by the WA Supreme Court in August last year.

Mr Ryan’s report urges the WA Department of Justice to “rethink and reimagine the staffing model”, detailing how the daily staff shortages were “unprecedented”, that attrition was “unsustainable”, and that recruitment was struggling to “keep pace”.

Mr Ryan said it was clear that what has been tried to date has not worked.

“The staff at Banksia Hill and Unit 18 are doing the best job they can in the most difficult of circumstances. Under the current staffing model, the only way to provide safety for young people when there are not enough staff is by being locked in cell,” he said.

“It is a self-perpetuating cycle because the young people’s isolation increases their anxieties, anger and frustration and sometimes they act out negatively to themselves and others,” he said.

“When staff respond to these incidents, this often leads to more and longer lockdowns. The help these young people need and the effective rehabilitation they require are exactly the types of interventions – education, programs, recreation, training, family reconnection and general health and mental health – that have been most heavily impacted by staffing shortages and increased lockdowns.”

Mr Ryan noted that the issues and concerns the team observed during the inspection meant he has taken an “unusual approach” to his reporting requirements:

“In the public interest of speeding up our reporting, this is an inspection report in two parts,” he said.

“Part One focusses almost entirely on the immediate crises. It proposes 10 practical recommendations and I credit the Department for supporting the majority.

“For Part Two, we had hoped to examine the range of rehabilitative supports, interventions and initiatives that we heard about during the inspection. These ‘green shoots’ were simply inaccessible at the time due to severe staffing shortages. But I am reconsidering the merits of Part Two since the most recent riot. The events of May 9 and 10 have been an enormous setback for the centre.”

Mr Ryan said “much of the work the Department had been trying to do has been undone”.

“And so, our planned approach will depend on our close monitoring of the situation in the coming weeks and months. We wait to see what type of daily routine can operate and what level of service delivery is possible, acknowledging that a new school of probationary officers commenced in late-May 2023.”

Mr Ryan again called on the Western Australian Government to commit to a second youth custodial facility.

“Banksia Hill as the one-size-fits-all approach does not work, and the use of Unit 18 demonstrates the need for a smaller facility for those with complex behavioural needs,” he said.

Mr Ryan acknowledged that “it would not be an immediate fix to any of the current issues but that it was likely to address the medium to long term needs of youth detention in Western Australia”.

WA also has no remand centre for youth, meaning incarcerated children who have been charged but not convicted are held at Banksia Hill.

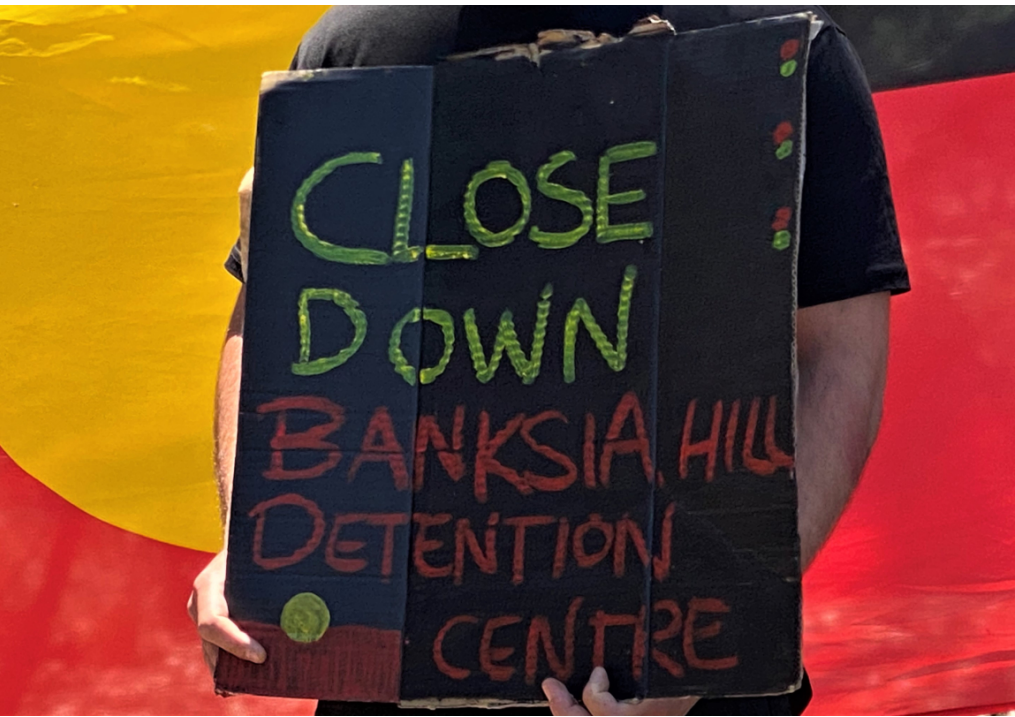

Kurin Minang human rights expert, law academic and member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Dr Hannah McGlade, told National Indigenous Times the use of confinement in Banksia Hill was “extremely dangerous”.

“The Inspector highlights the urgency of the situation at Banksia Hill, the ongoing crisis,” she said.

“The report documented the use of solitary confinement of children every day of a 10-day inspection, which is extremely dangerous and prohibited under United Nations human rights law.”

Dr McGlade said Aboriginal justice advocates “wish to explore with the state government Aboriginal cultural and therapeutic responses to youth justice”.

“The cycle must be broken, and this will only happen when the state engages with us, respecting the principles of self-determination and cultural rights.”

The Department of Justice said it “welcomed” the latest inspection of youth detention facilities.

“Despite the significant impact of the (May 9-10) incident at Banksia Hill, recommendations in the report continue to be actioned to improve staffing levels, safety and the care of young people,” the Department said in a statement.

“Eight out of 10 recommendations were supported with work to address behaviour management, Aboriginal staffing, detention centre charges, ‘safe exits’ for staff, rostering and vocational training well progressed. Efforts to recruit and retain staff also continue.”

The Department said four additional Youth Custodial Officer training programs are expected to be held this year, providing up to an additional 80 YCOs for Banksia Hill, in addition to the 37 new YCOs who commenced work in May.

The Department said positions in the new 13-person Aboriginal Services Unit are “now mostly filled”.

It said the new model of care and trauma-informed operating philosophy will see multidisciplinary teams of mentors, Aboriginal support officers, psychologists and other specialists working together to assist young people’s rehabilitation journey.

“A new behaviour management scheme is being developed, and alternatives to the ‘safe exit’ technique are being tested.”

Department Director General Dr Adam Tomison said “the work we have underway to boost staff numbers, implement a new model of care and better manage detainee behaviour is reflected in OICS’ recommendations”.

“There is a substantial amount of work still to do, but we are confident the $90 million-plus investment in infrastructure, staff, services and a new Crisis Care Unit will address many of these difficult issues,” Dr Tomison said.

Commissioner of Corrective Services Mike Reynolds said the report recognised the commitment of staff working in youth detention.

“While the significant challenge in running these facilities is understood, the Department is confident the implementation of its new model of care will transform management of the centre,” he said.

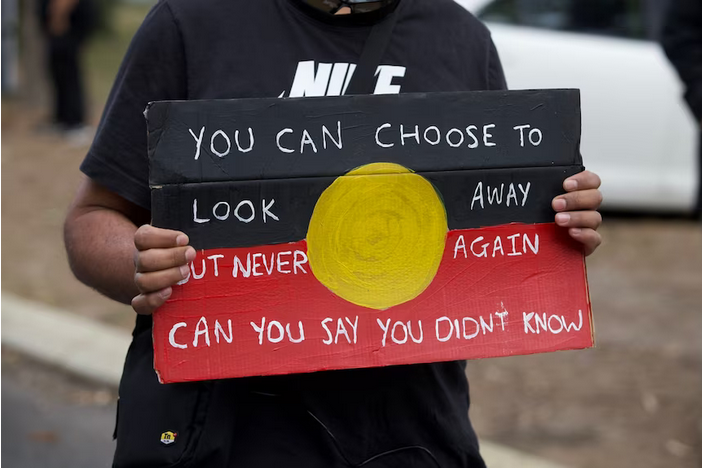

Megan Krakouer from the National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project, which collected testimonies from hundreds of former Banksia Hill detainees for a class action, told National Indigenous Times it was time to “call a spade a spade”.

“The Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services has been operating for two decades and it is on their watch too, along with the Children’s Commissioners and other titled-up state scions. The turnstile of ineffective wasteful parliamentary inquiries cannot end the crises and the trainwreck lives that end in suicide and adult prisons,” she said.

“Shame on these so called watchdogs and bureaucrats. If it was not for… stalwart social justice reformer, Gerry Georgatos, and lawyers Stewart and Dana Levitt and the class actions, all would have been swept under the carpet as has been for decades.”

Ms Krakouer renewed her call for Mr Georgatos to be involved in addressing the crisis in Banksia Hill.

“He delivered in Banksia in eight weeks in 2020… what brand name services spent years failing to do. Gerry led change in nine months in Acacia, between October 2020 to June 2021, reducing First Nations self harm incidences to the lowest ever,” she said.